What’s Causing Your Pain After Pilates?

Here is a quick recap of part 1 in the Pilates Pain series:

We chatted about why Pilates hurts sometimes, looking at the front line – a track of muscles and fascia that runs the length of the front of your body. When this line is overactive (or a little wonky), it can alter movement patterns and lead to neck, back, and hip pain.

We also chatted about spinal flexion, think crunches, roll-downs, and teasers. While flexion isn’t inherently bad, it can lead to trouble if you can’t fully move out of a flexion pattern (hello desk life).

Now that we are all caught up, let’s jump back in. In this article we will get into the nitty gritty of pain from Pilates:

✅ Muscle Overuse & Imbalances

✅ Fascial Tension & Restrictions

✅ Nervous System Sensitivity

What’s happening in your body

The most common patterns you’ll see in Pilates work are Spinal flexion, hip flexion, and core-centric moves (aka more flexion). All of these can increase pressure on the lumbar discs. This increased pressure will feel like low back pain after a workout.

When pain comes during or after Pilates it can indicate that your movement patterns, muscle balance, and load distribution need some fine tuning. Let’s look at big concepts that lead to pain.

Muscle Overuse & Imbalances

Let’s start with some basics: Muscles move you, but you know that not all muscles move us in the same way. Some are more subtle, and others have that theatre kid-like energy. All of them are important. Another way to say this is that some muscles have a tendency towards stabilization, while others have a tendency towards mobilization. But each can switch roles if necessary. Wonky movement patterns, and pain can happen when stabilizing muscles are injured or not working to their best capacity. When this happens, mobilizing muscles have to act like stabilizers, and boooooyyyy they do not like that. Have you ever told a theatre kid to tone it down?

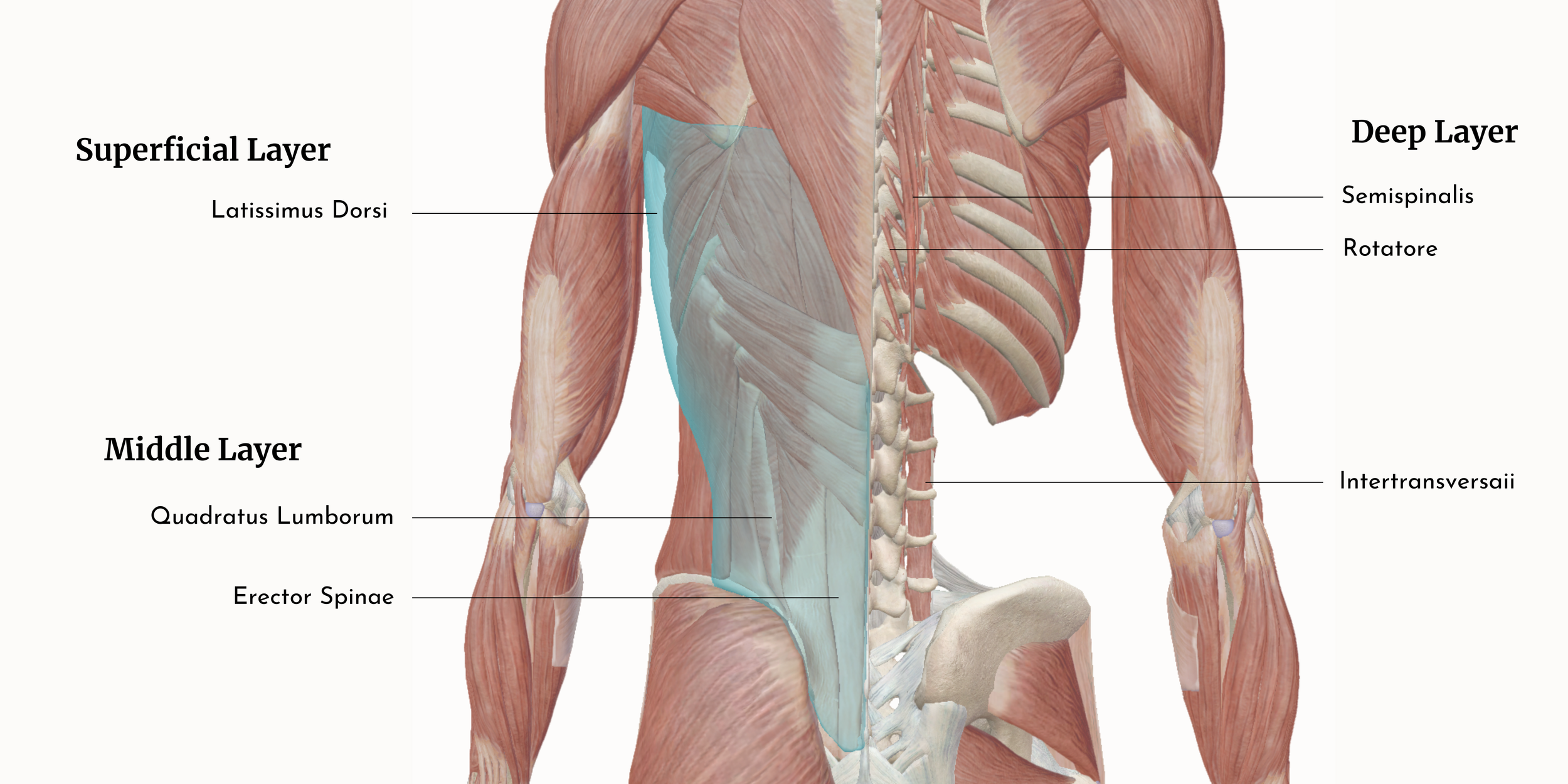

Stabilizer muscles are small muscles that cross a single joint close to the joint articulation. Whereas mobilizer muscles are big muscles that sometimes cross multiple joints and are more superficial. Take the Latissimus Dorsi vs the Quadratus Lumborm vs Erector Spinae vs the Intertransversarii

When these big mobilizer muscles try to work as stabilizers, you’ll get altered biomechanics at lots of joints (‘cause they are big, and span big swaths of your body). That then leads to altered movement patterns, overuse, fatigue, and pain.

Researchers have also found that big mobilizers do a pretty terrible job at stabilizing (here). Take the superficial front line (mobilizers) vs the deep front line (stabilizers) as a great example.

The superficial line has the super sexy Rectus Abdominis, aka the 6 pack muscle. It might be working its buns off to keep you steady, but if even 1 section of stabilizers are not working properly, your lumbar spine will be “as unstable as if it had no muscles at all” (pelvic girdle). Aaaannndddd the rectus abdominis completely fails at keeping you injury free!

Some muscles (like your hip flexors or neck muscles) might be overworking, while stabilizing muscles (like your deep core or glutes) are under-recruited. This imbalance leads to lack of motion through your full range of motion.

We all want a quick and easy answer to why our bodies hurt, but you need to consider your body as a whole. The likelihood is that it is multiple compensations, and multiple muscles and layers being affected.

If there was a clear answer, then there would be a clear solution like “your bicep is weak, train that muscle and you wont have pain any more” but that’s not really how our bodies work. Your body is a community and all your muscles work together.

Fascial Tension & Restrictions

Before I get into how fascia can lead to pain after a Pilates class, I wanted to get one thing out of the way:

What is fascia?

Fascia is everywhere, it helps our organs and muscles glide and slide across each other. It wraps around muscles, organs, nerves, bones, and vessels — it’s continuous and found throughout our body, it gives shape and support to internal structures.

Fascia is strong and supportive, while also being flexible and adaptable. it can change its shape under mechanical stress, pressure, or load. It can bounce back after being stretched, or adapt and retain a new shape to meet new demands.

I used to think of fascia as a solid layer, kind of fabric-like – thick and dense. But really it's more like a dynamic, goopy, sloppy, slippery spider web that responds to how you move.

When fascia is healthy it’s mobile, dynamic, and hydrated. When it becomes tight, dehydrated or bound the result is a fascial restriction. Fascial restrictions are often due to old injuries, inflammation, overuse, surgery, immobility, stress, or repetitive movements (AKA physical trauma or habit).

These restrictions and tension can have cascading effects throughout your body. In my clinic I often describe it like picking up your kid's mess. You can consciously decide to pick something up, but you can’t choose what joints you use. If you have a restriction in your upper back, maybe your arm has to reach further, or maybe your low back compensates. Fascial restrictions interfere with the ability of tissues to slide and glide, which then leads to compensations in other areas of your body.

Your body will try to compensate for restricted fascia by recruiting other muscles or joints to do the work of the restricted area. This can cause fatigue, dysfunction, or strain elsewhere.

These changes and compensations can directly impact movement quality, increase pain sensitivity (we’ll talk about that in the next section), and interfere with body mechanics — all of which show up in how people feel and move during Pilates (or daily life!).

Because nerves, arteries, veins, and lymphatic travel through fascia, when fascia is restricted, it can interfere with the functioning of those vessels. It may interfere with the inflammatory process (AKA healing response).

Nervous System Sensitivity

In the last section we chatted about how fascia is this protective, transportive material that is alive, and that’s actually really cool. Now it's time to chat about how it's alive.

On the somatic/ motor/ muscle side of nerves fascia is deeply innervated (supplied with nerves). It has:

Mechanoreceptors - sends mechanical information to the brain - eg. how much pressure your arm is receiving

Proprioceptors - sends positional information to the brain - eg. where your arm is in space

Nociceptors - sends pain information to the brain - eg. that acupuncture needle hurts a tiny bit.

All this information makes your fascia a huge sensory organ, collecting, processing, and sending information. It also means that fascia plays a major role in coordination.

On the other hand, it also has an intimate relationship with the autonomic nervous system. These nerves control blood flow (hello healing + tissue recovery!), the inflammatory response (which relates to the size of the blood vessel), and tissue tension regulation!

Then on top of all that, nerves are wrapped in fascia and continuous with the fascia of the surrounding tissue. When fascia loses its gooey glide and becomes tight, it can impact the nerves ability to collect, process, and send information. And can also contribute to nerve irritation (AKA pain).

The biggest symptoms I see in my clinic that relate this are tingling, numbness, burning, and muscle weakness. So maybe your glutes aren't weak, maybe your inferior gluteal nerve is bound up.

Any disruption to fascia’s normal functioning easily gets translated into pain because there are so many pain receptors (nociceptors) found in fascia. So things like tightness, inflammation, dehydration can cause reduced range of motion, both muscle contractions and muscle weakness, and can have knock on effects throughout the body.

Repetitive motion, strain, trauma, and inflammation can make your nerves more sensitive—especially when fascia isn’t functioning properly. When fascia becomes stiff or "sticky" due to chronic inflammation, fibrosis, or habitual poor posture, it limits the easy glide between muscle layers and reduces overall tissue mobility. This restriction disrupts the smooth communication between nerves and muscles, alters proprioception, and can contribute to myofascial pain. Essentially, when fascia can't move well, neither can your body—or your nervous system.

Research shows that proprioceptive deficits—essentially, a lack of clear feedback from your body’s positional sensors—are linked to spinal disorders and an increased risk of injury. When proprioception is impaired, your movements can become less precise, increasing strain on muscles and joints. One study found that individuals with a history of low back injuries had reduced lumbar flexibility and altered proprioception, making them more prone to further issues. (Here)

OMG, there is actually so much more I could write about fascia, the nervous system, and their relationship to pain, but alas, I think this is enough for now.

Reframing perspectives

Pain during or after Pilates isn’t your body being dramatic or failing you—it’s your body being informative. It’s saying, “Hey friend, something in here needs a little attention.” And while that might feel frustrating (especially when you’re just trying to get strong and feel good), it’s also an amazing opportunity to get curious and practice listening.

What if pain isn’t the villain, but a helpful messenger? What if your glutes aren’t lazy, your core isn’t weak, and your body isn’t broken—just a bit out of sync? When we reframe pain as feedback (rather than failure), we can create space for healing, and a deeper connection to how we move and live in our bodies.

In this article, we unpacked how muscle imbalances, fascial restrictions, and nervous system sensitivity can all contribute to discomfort in Pilates. These systems are incredibly interconnected, and when one gets out of rhythm, the others have to pick up the slack. The good news? Your body is wildly adaptable—and with the right support, it can relearn how to move with ease.

If you’re finding that Pilates brings more pain than pleasure, you’re not alone—and you’re not stuck. A movement-savvy Osteopathic Manual Practitioner (👋 hi!) can help you decode what’s happening under the surface, so you can move with more freedom, less pain, and a whole lot more confidence.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this series where we’ll explore common symptoms and how to approach your Pilates practice (and recovery) to support a more pain-free experience—without tossing your teaser to the curb.

-

Cholewicki, J., & McGill, S. M. (1996). Mechanical stability of the in vivo lumbar spine: implications for injury and chronic low back pain. Clinical biomechanics, 11(1), 1-15.

Langevin, H. M. (2021). Fascia mobility, proprioception, and myofascial pain. Life, 11(7), 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11070668

Parkhurst, T. M., & Burnett, C. N. (1994). Injury and proprioception in the lower back. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 19(5), 282-295.

Merkle, S. L., Sluka, K. A., & Frey-Law, L. A. (2020). The interaction between pain and movement. Journal of Hand Therapy, 33(1), 60-66.

Willard, F. H., Fossum, C., & Standley, P. R. (2010). The fascial system of the body. In R. C. Ward, R. J. Hruby, & J. A. Jerome (Eds.), Foundations of osteopathic medicine (3rd ed., pp. 111–125). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Fundamentals of osteopathic education: A syllabus (Vol. 1). (n.d.).

Have questions about muscles, spinal mechanics, and pain?

Shoot me an email or book an appointment!